Zcash Wallet Report

The first phase of the ZeWIF project, to create a Zcash Extensible Wallet Interchange Format, involved undertaking a survey of existing wallets and then summarizing that survey with a spreadsheet and this report. The initial surveys involved looking at six major wallets: Zcashd, Zecwallet, Zingo, eZcash, Zashi, and Ywallet. The results are all available online. A spreadsheet then crossreferenced the data, with the intent of categorizing data for potential inclusion in a ZeWIF format and highlighting data that was frequently repeated on different wallets. A 1/24/25 meeting further supplemented this initial work by inviting commentary from experts on the categorization to that point.

The ZeWIF project is being undertaken by Blockchain Commons and Zingo Labs under a Zcash Community Grant. Its goal is to create an interchange format for Zcash wallets, immediately to support the Zcashd deprecation but in the longer term to create more freedom for users by improving interoperability, an important Gordian principle.

ZeWIF wallet surveys courtesy of @dorianvp from Zingo Labs, categorization and this report by @shannona from Blockchain Commons.

Categorizing the Data

The Zcash Wallet Content spreadsheet broadly organizes wallet data into 9 categories: seeds, keys, addresses, accounts, contacts, transactions, state, config, and authentication. Its intent is to create a master listing of core data in wallets and in doing so to highlight the most important data. This is done so that the ZeWIF wallet specification can prioritize data into three levels.

- First class data. Data to be included in the core specification, likely with CBOR tags assigned to ensure the data is self-documenting.

- Second class data. Data considered important enough to store in an easily accessible format, but not important enough to make part of the core specification. Best practices will suggest this data be encoded as attachments.

- Third class data. Data that is not stored, except as part of the backup of the wallet file, which best practices suggest be kept as part of the ZeWIF file.

The following comments discuss most of the major categories of data outlined in the spreadsheet, following a few general observations on encoding.

Encoding Notes

Though Zcash is just past its eighth birthday at the time of this writing, this is a huge amount of variety in both the data that’s stored in wallets and how it’s stored. The latter may prove to be one of the biggest challenges for creating ZeWIF data.

To a certain extent, reading existing data is an implementation detail: the purpose of the ZeWIF project is to create an interchange format and to provide developers with the tools needed for them to convert their own data into the interchange format. However, vastly different data storage methods can also create very different types of data.

- Flat Data. The traditional

wallet.datfile is a flat file with data often serialized into a key-value format, as is the case with Zcashd. - Hierarchical Data. Other wallets such as eZcash use a hierarchical data format.

- Database. Finally, wallets such as Zashi and Ywallet utilize a relational database with interlinked tables.

Creating a single specification that can easily accommodate these many data models, with different ideas of hierarchy and abstraction, is challenging, but is one of the reasons that the Gordian Envelope data format was chosen as a foundation, as its design using semantic triples has already proving effective at modeling a variety of different data types.

Seeds & Keys

Seeds and keys, which are obviously the heart of any wallet, were also flagged as an early data challenge, due to the proliferation of address types (transparent, sprout, sapling, orchard) and due to the fact that early keys were created from system randomness while later keys were created using hierarchical deterministic (HD) protocols.

This definitely remains an implementation challenge. In particular, importing wallets will have to decide what to do with keys or key types that they do not support, and that might not even be modeled in their wallet design. (More on this in the best practices guide for conversions, but the general suggestion will be: always tell users about everything that isn’t fully converted.)

However, this may prove to be one of the easier categories for actual specification. The various seed usages and the various key types are all well understood and most importantly their usage is fairly standardized because they all should follow Zcash specifications. As a result, the biggest challenge here will likely be creating a hierarchical organization within ZeWIF that matches how the keys and seeds are used and derived, and therefore makes it easy for importers to see how data is related and to fill in the gaps when some keys were not previously generated.

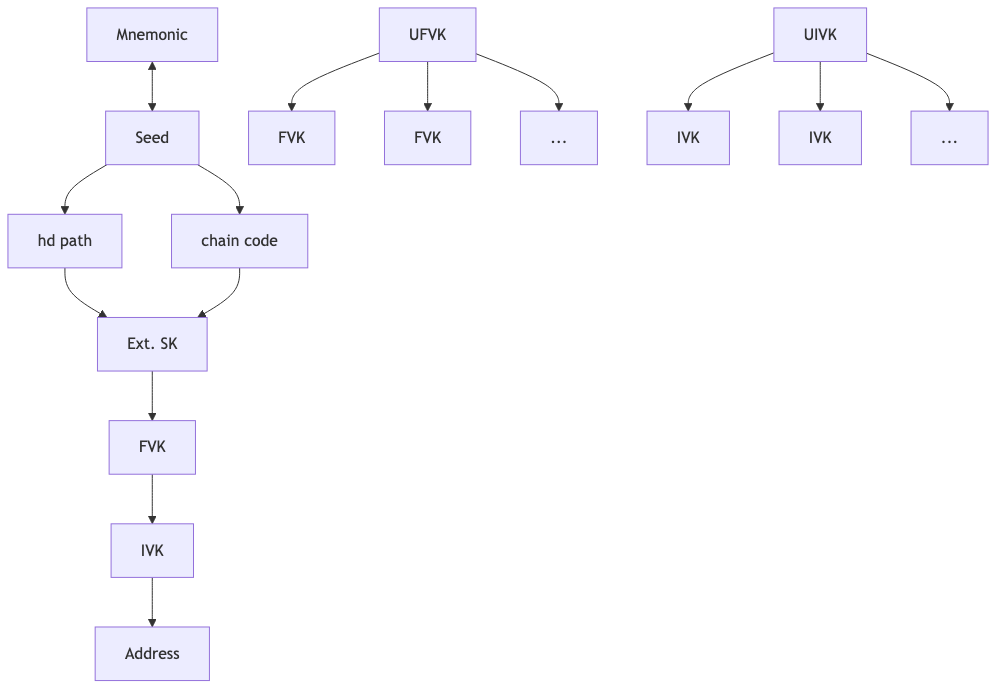

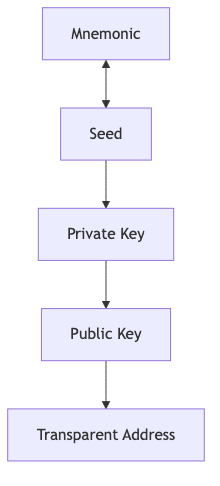

The following models are in no ways final, but suggest the types of hierarchy that will likely need to be created.

Shielded Addresses:

Transparent Addresses:

Addresses

Though many addresses may be derived from keys in an account, there are actually a variety of sorts of addresses found in wallets:

- Fully controlled addresses created from seeds or master keys in the wallet.

- Viewing-only addresses created from viewing keys in the wallet.

- Remote addresses appearing in contact books.

- Remote addresses to which funds were sent.

Though all sorts of addresses will likely be recorded using the same data abstraction in ZeWIF, these four major types of addresses may need to be organized in different ways.

Metadata

Metadata for seeds, keys, and addresses was flagged as another major challenge in the design of ZeWIF as it was expected to vary widely between different wallets.

Key-related metadata was somewhat more simple than expected. Major categories include:

- Creation time

- Key type

- HD information

- Seed fingerprint

Address-related metadata had more of the expected diversity, including:

- Diversifier information

- Viewing keys

- User-supplied description of address

- User-supplied dame for address

- Transactions in which address was used

-

Accounts

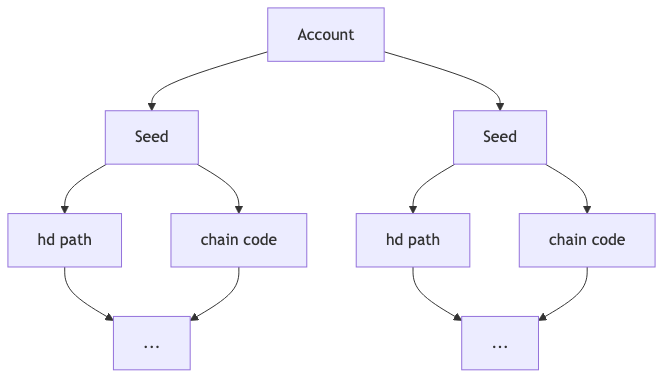

There’s another important element for seeds, keys, and addresses: accounts. Though accounts are described in ZIP-32 as an element of hierarchical key creation, the usage of an account abstraction goes far beyond that and might be used by any wallet to group together any group of keys, whether they’re truly related or not. These abstractions should be maintained in any ZeWIF format. Whether an account represents a cryptographic relationship or not, it represents the user’s understanding of how their funds are organized, and so how they can be spent.

Accounts should therefore be understood to be parts of the hierarchies of keys and addresses.

Account metadata might include key sources, HD and chain information, birthdates, deathdates (after which an account’s keys are not used), names, descriptions, and other informations. Accounts were extremely varied from one wallet to another, as described in the wallet-data spreadsheet.

Besides seeds, keys, and addresses, transactions can also be associated with accounts.

Transactions

Many wallets in the blockchain ecosystem keep track of transactions so that they have an easy reference for fund transfers that involved the wallet and/or to hold copies of that transaction information local to the wallet.

However, Zcash wallets have a much higher need to track transactions because of Zcash’s shielded addresses, which hide the senders’ and receivers’ addresses, the transaction amount, and the Zcash memo field. The desire to record this information, to record viewing keys, and to record the cryptographic elements that create addresses has resulted in Zcash wallets holding far more transaction information than a typical blockchain wallet and for that information to be much more important. Unfortunately, what data is stored and how it’s stored is also fairy inconsistent due to a combination of Zcash’s innovation and no previous attempt to standardize this crucial information.

This will result in transaction modeling being another challenging aspect in the ZeWIF specification.

Though there was some early discussion about whether transaction information that was freely available on the blockchain should be recorded in the ZeWIF format, thanks to the expert advice at the first ZeWIF meeting, we were able to decide that the best-practices answer was “YES”. This ensures the best consistency, avoids the whole question of whether data is recoverable or not (and more importantly an implementer mistakenly omitting something that was not recoverable), and supports privacy by avoiding the disclosure that could occur from redownloading select transactions from the blockchain.

The ZeWIF specification will likely include fairly comprehensive modeling for transactions as a result, and our best practice suggestion will be to fully encode transactions from wallets, and perhaps even to incorporate missing data from the blockchain (though again, there might be privacy issues here, and best practices likely would give the user a choice). However, special care must still be given to that data that is not recoverable, including not just information that is hidden in shielded transactions, but also other metadata such as current price that isn’t recoverable or at the least isn’t easily recoverable.

Finally, it should be noted that some wallets save information for transactions that were not successfully mined. This should be incorporated as part of the ZeWIF specification.

Memos

Zcash memos fulfill one of the major purposes of metadata: describing transactions. This will likely simplify some ZeWIF elements.

However, the vocabulary for “notes” and “memos”, both described in ZIP 302, causes some threat of overloading.

The term “annotation” has therefore been used in the spreadsheet for a local annotation made by a user, which may not also be a memo on the blockchain.

State & Config

Wallets often contain information on current state and on wallet configuration. This data is almost entirely likely to be second or third class, as it really doesn’t matter what your “spam threshold” was on your previous wallet or if your wallet has a complete download of years’ worth of prices.

Two bits of data have been flagged for special consideration in this category.

The first is wallet and version. Best practice should be to preserve entire strings of this data to show the whole history of a wallet data file. This may be best accomplished by making it a first-class data type.

The second is the commitment trees. Though these are theoretically recoverable, they’re fiddly, so preserving them as a best practice (and with solid definition in the specification) will ease the effort required by importers. However, it would also be best practice to drop a commitment tree on import if it’s incorrect.

Authentication

A few wallets used encryption keys, wallet keys, or nonces to protect the sensitive data within the wallet. Our current best practice suggestion is that data should be decrypted as part of the export from the wallet, because otherwise its resilience is notably decreased (e.g., it would be easy to lose the data).

The Envelope data format that will be used for ZeWIF allows for the simple encryption of its data with the envelope-cli. Best practice suggestion will be to use this encryption that is native to Envelope if ZeWIF data is to be stored at rest. This improves resiliency because there will be one standard for encryption, not a half-dozen. (Best practices will also offer some suggestions on how to keep that key safe!)

Missing Categories

The main category of information that we expected to find but did not in any of the six wallet formats that were examined was backup information. Single-sig private keys are fragile, with loss being the main threat to the average user. It’s important to back them up via methods such as sharding using Shamir’s Secret Sharing or engaging in simpler (but less secure) backups such as storing in NFC tags or even engraving on metal plates. It’s equally important to leave pointers on a wallet to reveal where backups are.

Though backups of this sort could be encouraged but not recorded in some of these wallets, we generally suspect that the Zcash ecosystem could benefit from secure backup methods such as SSKR, which uses an advanced form of Shamir’s Secret Sharing, and a network of Collaborative Share Recovery (CSR) servers, but that goes beyond the scope of this project.

Final Notes

The first phase of the ZeWIF project focused on surveying existing wallets and charting out and analyzing that data. This work is intended to be a tool in the development of a ZeWIF specification that supports the diversity of the Zcash ecosystem, that avoids embedding legacy data in the core specification, and that future-proofs itself so that it will be usable far into the future.

The ZeWIF specification, which will be created in phase two, is the true end result of this, but in the meantime the initial phase of the project has not only exposed much of the information for incorporation into a specification, but also highlighted important elements such as:

- Data may not just be flowing in from traditional flat files, but also hierarchical structures and databases.

- Accounts are an important abstraction that should likely be a top level data element.

- Accounts, seeds, and keys should likely be arranged into hierarchies.

- Addresses need to be flagged for different types, particularly receiving addresses and contact addresses.

- Transactions may be the most complex modeling primarily due to the different shielded info that’s stored by different wallets in different ways.

- Metadata for all core data types should be considered. There’s a fair amount of similarity for much (but not all) of the metadata, suggesting that a lot of it may be encodable as first-class data.

- State and config can generally be downgraded to lesser data classes, with wallet version and commitment trees being the main things flagged otherwise.

- Data might be encrypted within existing wallets, but it should generally be decrypted before ZeWIF encoding.

We look forward to continuing on with the creation of the actual specification.