Progressive Trust is one of the keystones in Blockchain Commons’ architecture. It posits that digital trust needs to be modeled after how human trust works in the real world. Traditionally, people came together in a medium where their personal data was innately minimized and gradually got to knew each other until they’d developed sufficient trust to engage in some interaction for mutual benefit, which could be anything from hiring someone as a contractor to marrying them. As social psychologist James W. Pennebaker said, “Conversations are like dances.” It’s a mature process that evolved over thousands of years.

“The basic idea behind progressive trust is to model how trust works in the real world” —Christopher Allen, Musings of a Trust Architect: Progressive Trust (December 2022)

Perhaps the internet was like that in its early days, when you met someone on a MUD or engaged in a talk and learned more about them over time. But when the internet became commercialized in the ’90s, powerful institutions brought new models for interactivity. They gained economic benefit from limiting what you could see. This allowed them to simplify usability and to create their own controlled communities, all of which increased their commercial viability, so limit they did. That’s the internet that exists today. Centralized entities offer you restricted views of your fellows and provide binary choices on silver platters: trust or not. There are no shades of gray, there is no progression. Decisions are really made by them, not us.

Web browsers offer an example. They tell us who to trust on the internet, but they do so without nuance. They tell us sites that have been able to acquire certificates, legimately or illegimately. They don’t tell us sites with a record of stability, they don’t tell us sites with a reputation for truth, and they definitely don’t tell us who to trust on those sites. This is just one of the places that progressive trust can benefit the internet, for trust isn’t black and white: it exists in a world of gray.

Fortunately, the wheel is turning again. The modern internet offers distributed and decentralized systems that put choice back into the hands of individuals, allowing them to make decisions without the coercion, censorship, and unbalanced power of centralized systems. This allows the creation of systems where a user isn’t served up binary choices for trust based on limited information. Technologies such as data minimization and selective disclosure improve the situation even more. They can further protect our human dignity and choice by letting us choose to slowly (progressively) reveal our own information over time. We just need to normalize these technologies and apply them to human interactions that have been warped by the 21st century corpocratic control of the internet. We need to apply them fully in order to fully trust.

“Adapt Locally … Govern Locally” —Christopher Allen, 10 Design Principles for Governing the Commons

What follows is a life cycle that demonstrates the steps of progressive trust that are simultaneously automatic in the real world and ignored in the digital world. It includes use cases that demonstrate the important of progressive trust:

- Personal Contracts. Personal interactions are the ground level for progressive trust. The simple act of hiring a carpenter demonstrates its foundations. This is the default use case for this life cycle, and one that is purposefully written as existing in a physical (not digital) world.

- Journalistic Integrity. Journalists and newspapers must trust each other before they are willing to stake their reputations on each other.

- Bitcoin. The first successful e-cash system was also the first successful example of a progressive trust system.

- Wellness Data. Clinical studies want to access individual activity tracker data, and individuals want to support the public good.

- Educational Credentials. Credentials must be signed by trusted authories.

- Software Supply Chain. Software needs to be verified as free of malware and signed by appropriate developers to be trusted.

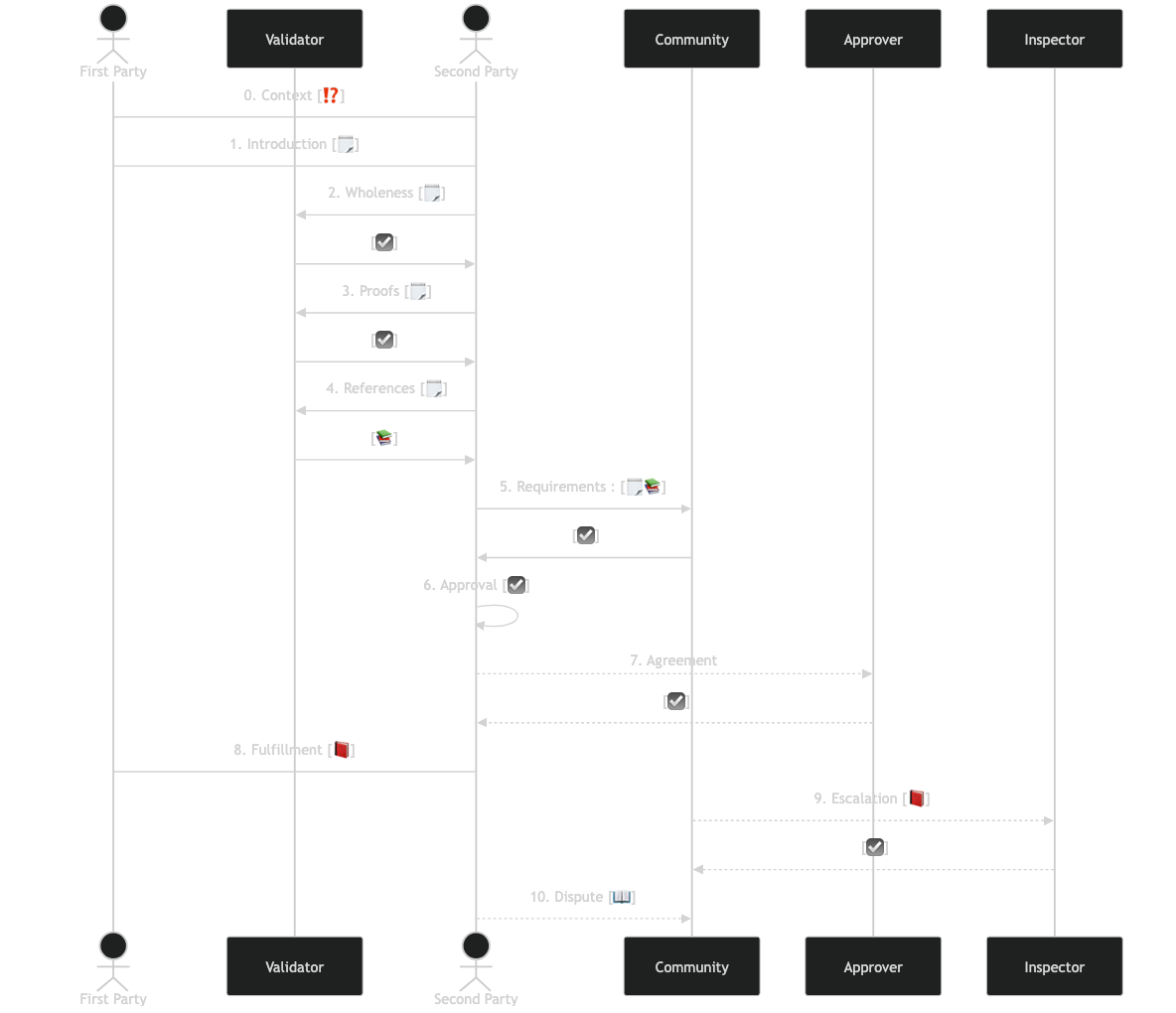

Life Cycle Overview

The following sequence digram roughly outlines the steps of the progressive trust life cycle:

There are three major caveats.

First, the phases are two-sided. Progressive Trust is the act of two parties coming together for mutual benefit. Though there is sometimes a power or reputation disparity (as between a green journalist and a newspaper of record), ultimately both parties must be satisfied with their partner. Thus in the diagram above, phases 1 & 8 are bipartite. Phases 2-7 and 9-10 may then be engaged in by both parties. A more complex (and harder to read) sequence digram would show each of the two parties engaging in each of those phases.

Second, this is an iterative process. Sometimes progressive trust will fail a test at some phase in this process, forcing the actors to go back to previous phases to gain sufficient trust to pass the tests. This is outlined in Success: descriptions of each phase.

Third, the goal of these phases is explicitly not to achieve binary trust, but to achieve trust in gradients of grayscale: each actor creates a trust model, compares it to their risk model, and decides if the trust is sufficient to offset the risk or not. That’s the whole purpose of Progressive Trust: to return things to this pragmatic assessment rather than the current model of trust on the internet, which primarily involves pushing “OK” buttons when Google says things are fine.

0. Context (Interaction Considered)

- Description: Contemplates an interaction that is intended to work in some mutually beneficial way, including its requirements and possible results and determines whether a progressive-trust model is required at all, or if some simpler, binary model of trust might be sufficient. Basically, if the interaction low-risk, low-cost, or low-value enough that you don’t need to go to the trouble of a complex progressive trust methodology?

- Actors: Two parties, individually.

- Action: Consider interaction and its environment. Determine if trust is needed, and if it is, determine if complex progressive trust methodology is required.

- Success: Progressive trust is needed!

- If progressive trust is not needed, use a no-trust, trustless, or binary-trust model, and ignore the rest of the phases in the progressive-trust model.

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Hank the Homeowner considers hiring someone to do some remodeling for his kitchen. He expects it’ll be a costly job that will have repercussions on his home for the rest of the time he lives there. In addition, he’ll need to give any contractors access to his home, likely even while he’s away at work. This is a prime example of a situation where a gradiated model of trust is going to need to be assessed against a risk model, thus there’s a need for progressive trust. Hank will also need to consider his budget, and otherwise ensure he’s ready to hire someone.

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms:

- Active Verbs. CONSIDER, plan, survey.

- Objects. INTERACTION, context, ecosystem, environment.

- Etymology:

- Context. Originally from the Latin “contexere”, meaning “to weave together.” It’s about looking at the overall gestalt of an interaction and determining the appropriate way forward.

- Interaction Considered. “Interact” is a relatively new, 19th century word, that means to “act on each other”. It has Latin roots. “Consider” is from the Latin “conidererare”, neaking “to look at closely”. This is the act of closely examining the way that two parties will work together.

- Key Terms:

1. Introduction (Assertions Declared)

- Description: Establishes the starting point for a trusted interaction by parties indicating a desire to work together and laying the groundwork for subsequent evaluations by revealing some information and eliding or obscuring other.

- Actors: Two parties.

- Action: Make public assertions, claims, and declarations. Outline desired interaction and reveal some data assets, ensuring transparency and setting expectations. Also, define encrypted or elided data or other secrets through the establishment of a path to a process to obtain the missing data.

- Success: Sufficient initial assertions, claims, and declarations are formally documented and available to provide a clear starting point for a trusted interaction.

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Hank meets Carla the Cabinet Maker at a picnic for their softball team. Hank talks to her about wanting to remodel his kitchen. Carla gives him her card and says to call to get some testimonials.

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms:

- Active Verbs. DECLARE, assert, commit, establish, introduce, reveal.

- Objects. ASSERTION, initial claim, inception commit, origin, public declaration.

- Reactive Verbs. ACCEPT.

- Etymology:

- Introduction. From the Latin “introducere”, meaning to “lead in” or “bring in”. Both participants are being brought in to a trusted interaction.

- Assertions Declared. The term “assert” comes from the Latin “assertus,” meaning “to claim,” while “declare” comes from “declarare,” meaning “to make clear.” Together “Assertions Declared” emphasizes the initial step of publicly or officially stating and clarifying key claims or intentions, setting a transparent foundation for subsequent interactions.

- Key Terms:

2. Wholeness (Integrity Assessed)

- Description: Checks the data assets laid as the foundation of an interaction to measure their quality and determine that they are technically correct and sufficiently whole.

- Actor: Either party acting as or interacting with a validator.

- Actions: Perform thorough checks to ensure the structure and format of data assets are intact, sufficiently complete, and meet expected standards. Check for consistency based on historical data, but not based on cryptographic checks.

- Success: The foundational structure, integrity, quality, and wholeness of the data assets are confirmed, ensuring they are well-formed and free from corruption.

- If data fails Integrity Assessment, a new Introduction is requested that is whole (phase 1).

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Hank examines Carla’s business card and sees that it’s professionally designed and printed. He verifies that it has expected data, such as a name, phone number, and licensed contractor # and that they fit the proper formats for that data. (Similarly, Carla has already assessed that Hank’s job matches her skillset and verified that he’s a real person. She’ll continue to mirror all of the progressive trust extensions in the following steps as well.)

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms:

- Preparatory Verbs. STRUCTURE, cohere, order, organize.

- Active Verbs. ASSESS.

- Deprecated Verbs. VALIDATE is widely used to refer to checking against rules-based correctness. That would place it in this phase. However, VALIDATE is a problematic verb because it is often confused with Verify and because it ensures a binary yes-or-no result that’s the opposite of progressive trust. It’s therefore omitted other than this reference.

- Objects. INTEGRITY, consistency, wholeness.

- Etymology:

- Wholeness. From the proto-Germanic “haila” meaning undamaged. This is data that is structurally sound.

- Integrity Assessed. The term “integrity” comes from “integritas,” meaning “whole” or “untouched,” indicating a state of being complete and unaltered (but the latter will be more relevant in the next phase). “Assessed” is derived from the Latin “assidere,” meaning “to sit by” or “assist in judging,” which implies evaluating or estimating the nature, quality, or ability of something. Together, “Integrity Assessed” emphasizes the careful examination and judgment to confirm that all elements are intact, reliable, and unblemished. It’s the first phase in progressive trust.

- Key Terms:

3. Proofs (Secrets Verified)

- Description: This step follows foundational wholeness verification and adds a layer of security by ensuring that cryptographic contents or other secrets are valid. This step demonstrates how modern technology really shines, because it’s made algorithmic checks of this sort possible. Non-cryptographic secrets can be checked as well.

- Actor: Either party acting as or interacting with a validator.

- Action: Verify secrets. Check non-cryptographic secrets via investigatory means. Authenticate hashes, signatures, zero-knowledge proofs, or other cryptographic methods to ensure that data hasn’t been tampered with.

- Success: Secrets are verified to confirm their authenticity, either by investigation or by cryptographic proof.

- If data fails Cryptography Verification, a new Introduction is requested with verifiable Proof (phase 1).

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Hank has called Carla to receive names and phone numbers for a few testimonials about her work. These testimonials are non-cryptographic secrets since they’re not publicly known. He looks up the names he’s been given in a phone book and verifies that they indeed correlate with the phone numbers.

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms:

- Preparatory Verbs. ENCODE, hash, sign.

- Active Verbs. VERIFY, authenticate.

- Objects. SECRET, hash, proof, signature

- Etymology:

- Proof. From the Latin ‘probare’, to test. This is the scientific method where something can be examined to produce a true or false result.

- Secrets Verified. “Secret” comes from the Latin “secretum” meaning “a thing hidden”. (Note that “cryptography” is closely related but with a different root: it comes from the Greek “kryptós,” meaning “hidden” or “secret,” combined with “graphia,” meaning “writing.”) The term “verify” is derived from the Latin “verificare,” meaning “to make true.” Together, “Secrets Verified” means determining that hidden things are true and confirms the truth and accuracy of introductory information, ensuring it is genuine, unaltered, and secure.

- Key Terms:

4. References (Trust Affirmed)

- Description: This step involves the collection from multiple sources of trust references declared within initial data assets, including certificates, endorsements, and other trust indicators, which together form a comprehensive view of trustworthiness to inform subsequent interactions. It may also involve collection of trust references from third parties not mentioned in the original Introduction. It’s likely that all trust references are not collected: a party collects until they feel that they have enough; they could always return to this step in the future if needed.

- Actor: Either party acting as or interacting with a validator.

- Action: Gather declarations from various sources according to your trust model, aggregating them to create a grayscale vision of trustworthiness, and use that to affirm trust. Stop when you have enough.

- Success: Sufficient trust declarations are collected to affirm the trustworthiness of the subject based on these external references.

- If insufficient trust declarations are collected, references may be rechecked until sufficient are collected (phase 4).

- If insufficient trust declarations are collected, a new Introduction may be requested with different or additional references (phase 1).

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Hank checks Carala’s contractor # in the state databasae and calls up her references for their testimonials. He calls up the phone number on her business card and affirms the professionalism of her office manager’s response. Finally, he asks friends and family to see if anyone has heard about her. He then synthesizes those responses into an overall (but not binary) picture that affirms her trustworthiness for this task.

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms:

- Preparatory Verbs. ENDORSE [entity].

- Active Verbs. AFFIRM, aggregate, check, look up, synthesize.

- Objects. TRUST, declarations, references, trust model.

- Etymology:

- References. From the Latin “referre”, meaning to carry back. In this case, carrying back information.

- Trust Affirmed. The term “trust” originates from the Old Norse “traust,” meaning “confidence” or “protection.” “Affirmed” comes from the Latin “affirmare”, meaing “to make steady, strengthen, confirm” (ad- “to” + firmare “make firm”). Together, “Trust Affirmed” emphasizes the gathering and synthesis of diverse trust data, to strengthen credibility and reliability, rather than making a binary judgment.

- Key Terms:

5. Requirements (Community Compliance)

- Description: Following validation of initial and linked data assets, collected references are audited for adherence to community standards, to determine how an interaction would fit into general expectations for the space. Compliance may be determined through peer-to-peer mechanisms (for communities); or through decisions from higher authorities (for hierarchical networks). This will often involve the revelation of additional data beyond the initial assets, which is a normative part of the progressive trust process.

- Actor: Either party interacting with a community of mutual benefit.

- Action: Audit whether the authenticated data assets meet related community standards, policies, and requirements, ensuring adherence to expected criteria. Request and authenticate additional data assets as necessary.

- Success: The content is deemed in compliance with community requirements.

- If data fails Community Compliance, it may be outright rejected or a new compliant Introduction may be requested (phase 1).

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Hank determines that Carla’s contractor # is indeed the standard to prove expertise for this sort of work. He requests a quote and verifies the costs fit within expectations for the work. He then requests a contract and compares it to sample contracts.

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms:

- Request Verbs. AUDIT [requirements], check [standards], request [requirements].

- Additional Parties. COMMUNITY, peers.

- Active Verbs. COMPLY, cerify, standardize, test.

- Objects. REQUIREMENTS, expectations, policies.

- Etymology:

- Requirements. From the Latin “requirere”, “to ask for (something needed)”.

- Community Compliance. The term “community” comes from the Latin “communitas,” meaning “a fellowship” or “a group with a common interest.” Compliance derives from the Vulgar Latin “complire”, which is to fulfill, making compliance the act of fulfilling. “Community Compliance” is thus the fulfillment of the needs of a group.

- Key Terms:

6. Approval (Risk Calculated)

- Description: Having done all of the third-party trust validation possible, progessively expanding trust with new data assets along the way, each actor must now decide whether they want to interact with the counterparty. Approval may be final or it may require additional threshold approval (optional phase 7).

- Actor: Both parties.

- Action: Examine gradiated grayscale trust model, calculate its risk focusing on real-world consequences and likelihoods, and compare that to the party’s own risk model and their goals and desires. Provide authority for approval, or initial authority if additional Agreement is required.

- Success: Risk level determined by progressive trust is determined to fit within risk model of party.

- If interaction fails risk assessment, it may be outright rejected or a new de-risked Introduction may be requested (phase 1).

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Hank and Carla sign a contract. Hank provides a deposit and Carla provides a start date.

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms:

- Active Verbs. APPROVE, authorize, OK.

- Objects. RELEASE.

- Related Verbs. CALCULATE [risk].

- Related Objects. RISK MODEL.

- Etymology:

- Approval. From the Latin “approbare”, meaning to “regard as good”. This is the act of determining something is good (or in this case whether an interaction lies within each party’s risk model).

- Risk Calculated. The Italian “riscare” means “run into danger,” and has uncertain origins. The Latin “calculare” means “to reckon, compute.” “Risk Calculated” is thus the computation of whether one will run into danger.

- Key Terms:

7. Agreement (Threshold Endorsed) [optional]

- Description: An actor obtains additional consent through agreements from additional entities until they reach a sufficient threshold. This is an optional step; many actors will skip straight to phase 8.

- Actor: Either party interacting with another entity.

- Action: Secure approval from additional entities until sufficient threshold is reached to support final agreement for an interaction.

- Success: External agreements are obtained.

- If insufficient agreements are collected, Threshold may be rechecked until sufficient are collected (phase 7).

- If insufficient agreements are collected, data may be outright rejected or a new Introduction may be requested that would receive Threshold approval (phase 1).

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Hank gets agreement from his wife, Heidi, over the cabinet work. Carla gets a permit from the city.

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms: agreement, endorse, threshold

- Request Verbs. REQUEST [approval].

- Additional Parties. SIGNER.

- Active Verbs. AGREE, endorse.

- Objects. THRESHOLD, release.

- Etymology:

- Agreement. From the Latin “gratum,” meaning “pleasing, welcome”. This is the determination of whether something is welcome to multiple parties.

- Threshold Endorsed. The word “threshold” has an unknown etymology, and it’s also evolved over time. The Old English “þrescold” was a door-sill, which is to say a boundary. A more modern definition abstracts that to mean “a level, rate, or amount at which something comes into effect.” The word “endorse” similarly evolved over the years, this time from the French “endosser”, which meant to write on something’s back (the “dorsal” side) and came to mean to approve something by writing on its back. That’s particularly relevant here because the endorsement is an addendum to the official agreement on the “front”. You put together those transformative words into “Threshold Endorsed” and you have a level over which additional approval occurs.

- Key Terms: agreement, endorse, threshold

8. Fulfillment (Interaction Finalized)

- Description: Finalizing an initial agreement and actually engaging in the interaction. This is the point of no return, after which the actors can’t simply walk away, possibly due to contracts, guarantees, warrantees, or other sorts of responsibility or maybe just due to the possibility of losing face.

- Actor: Both parties.

- Action: Engage in interaction, doing any work, making any payments, and offering any other exchanges that were agreed upon.

- Success: Interaction occurs per agreed upon rules.

- If interaction does not occur, actors may need to repeat the process (phase 8).

- If part of interaction does not occur, one actor may need to Dispute (phase 10).

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Carla does the work. Hank pays her.

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms: finalize, fulfillment, interaction.

- Active Verbs. FINALIZE, fulfill.

- Objects. INTERACTION.

- Etymology:

- Fulfillment. The Old English “fullfyllan” means “fill up”, while the Latin suffix “-ment” turns that from a verb into a noun.

- Interaction Finalized. Interact as we saw means to “act on each other”. Final is from the Latin “finalis”, meaning the end. Overall, this is about a finalization of the decision of how entities work work together for mutual benefit.

- Key Terms: finalize, fulfillment, interaction.

9. Escalation (Independently Inspected) [optional]

- Description: Following the initial fulfillment, a third party may be called in. Whether this is needed or not is determined by the risk model of the actors (going back to phase 6). A third party can determine whether the interaction occurred in compliance with the contract. In order to do so, the inspector may repeat some of the steps to date, including going through their own assessment and approval (as in steps 2-7). Alternatively, they may repackage or reuse the results of the interaction for their own purposes, more implicitly endorsing it.

- Actor: The community or either party interacting with an inspector.

- Action: Assess, approve, and potentially endorse the results of an interaction. Or reject it.

- Success: The interaction is independently endorsed.

- If interaction is not endorsed, Fulfillment (phase 8) may have to be repeated by the counterparty.

- If interaction is not endorsed, the actor requesting the Inspection may need to Dispute (phase 10).

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): A city inspector verifies that Carla’s work is up to code.

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms:

- Request Verbs. ESCALATE, request [inspection].

- Additional Parties. INDEPENDENT THIRD-PARTY.

- Active Verbs. INSPECT, approve, confirm.

- Etymology:

- Escalation From the escalator, and so it just means to raise up.

- Independently Inspected.“Independently” is derived from the Latin “independens,” meaning “not hanging from something,” indicating a state of being free from outside control or influence. “Inspected” is from the Latin “inspicere” meaning “look at” or “look into”. It implies a close examination. “Independently Inspected” is something that is looked at by some entity beyond the control of the two parties.

- Key Terms:

10. Dispute (Independently Arbitrated) [optional]

- Description: Something may go wrong in an interaction, which may require a third-party to step in to abitrate. In a progressive-trust interaction, this will often require the revelation of additional data for evidentiary purposes that was obscured or elided in phase 1.

- Actor: Either party, or even a third-party, interacting with an community arbitrator.

- Action: Reveal elided or obscured information, produce affidavits, and otherwise expand public knowledge as is necessary to settle disputes over interaction. Ultimately, determine who is liable and for what.

- Success: Revealed information matches hashes of original data, proving that it was the source of the original data. Or it wasn’t. Affidavits support resolution of dispute. Or they don’t. In either case, an arbiter is able to make a decision about how to proceed.

- Use Case (The Kitchen Remodeling): Hank’s 20 pound cat jumps on a cabinet and causes it to collapse. Hank and Carla reveal contracts and the arbiter combines that with public information from inspections and research into load capacities to determine Carla didn’t anchor the cabinets correctly. She is found liable for repair and damages. The information on this dispute may unfortunately come up when Carla’s References are checked in the future by another Actor (phase 4).

- Lexicon:

- Key Terms:

- Request Verbs. DISPUTE.

- Additional Parties. INDEPENDENT THIRD-PARTY.

- Active Verbs. ARBITRATE.

- Etymology:

- Dispute. From the Latin “dis-“ (separately) and “putare” (consider). It’s literally considering apart, which is a great description of arbitrating between two parties.

- Independently Arbitrated. As we’ve already seen, “Independently” means being free from outside control or influence. “Arbitrated” comes from the Latin “arbitratus”, which means to “give a decision”, so this is an independent decision.

- Key Terms:

Final Notes

Progressive trust is hard! We discover that this is the case with many real-world interactions when we try to translate them to a digital medium. That’s because we’ve often translating subconscious and automatic steps into programmatic phase.

But, progressive trust is also rewarding. It’s a process that we’ve developed over thousands of years of interacting with each other in civilized society. Revealing information, checking it, revealing more, and ultimately coming to an agreement: that’s how real-world interactions work. By remodeling that in the digital medium, we can bring digital interactions up to the same standards, and thus ensure they have the same chances of success.

Appendix I :Additional Use Cases

Journalistic Integrity

Phase 0: Context

Journalist Upton S. considers whether to begin an extensive investigation into the conditions in slaughterhouses. He thinks about the possible benefits and the costs in doing so, and also surveys the publishing ecosystem, to see if anyone has enough independence to publish such an exposé.

Phase 1: Introduction

Upton takes (secret) photographs, interviews slaughterhouse workers and owners, and logs all those sources. He then writes an article based on that material.

Upton pitches the article to The Chicago Tribune. He includes the full article, the photographs with location and time partially obscured (to protect privacy), and the source interviews entirely elided. Hashes are available for everything, whether it’s elided or not. Upton personally signs both his obscured content (to record the changes) and the data package as a whole.

Phase 2: Wholeness

The Tribune has a required data format for prospective articles to avoid spam and AI submissions. They verify that Upton’s proposal matches the expected submission format, that hashes are present for all data, and that signatures are present for the overall package and for any altered data, to maintain the transparency of the materials.

Phase 3: Proof

Much of Upton’s data can be verified cryptographically. The Tribune verifies the signatures that Upton’s camera placed on his photos as well as the signature he himself made for obscurations and the whole package.

Upton has in the meantime required that The Tribune sign messages sent to gun with their private key, which he has been able to verify against a PKI, so he knows he’s talking to The Tribune and not a slaughterhouse owner in disguise.

This makes Upton feel comfortable enough to reveal additional secrets: he tells The Tribune exactly what slaughterhouses he visited and reveals GPS data that proves that he (or at least his phone) was indeed at those locations. (He still obscures the timestamps so that they’re only accurate to the month, so as not to endanger slaughterhouse workers who assisted him).

Phase 4: References

The Tribune affirms all references in the data package. For photographs, this likely means looking at a root certificate for the camera. For Upton’s signatures, this means checking his public key and any DID information. Some of these references may have another layer of certification and endorsement: The Tribune’s validator must recursively dig through it until they have the complete picture.

Since this would be a major exposé, The Tribune goes the extra mile and also investigates Upton’s previous publication of four well-received novels and even reaches out to Columbia University where he matriculated.

Upton meanwhile continues his own trust investigation as well, talking with journalists about how The Chicago Tribune has treated them and their sources.

Phase 5: Requirements

Due to progressively increasing trust, Upton again reveals more information to The Tribune, this time writing an essay on how he gathered his information by working incognito in slaughterhouses for more than a year. The Tribune dutifully hashes and elides this data so that it can be proven later if required.

Upton’s editor, Joseph M., is a little uncomfortable with the deceit implicit in Upton’s working incognito and has to check this against community standards. He finally decides it’s OK because Upton states (and creates a signed statement) that he fulfilled his contractual obligations to the slaughterhouse while doing so.

Joe also notes a few places in the article where claims aren’t backed up by sufficient sources, which is definitely in violation of community standards. Upton cuts a few, but is able to support the others. This results in the Introduction of a new draft, which must be checked for Wholeness, Proof, References, and ultimately Requirements, resulting in a partial repeat of Phases 1-5.

Phase 6: Approval

Joe makes a final determination of the credibility of all of Upton’s sources and information. He compares that trust model to his risk model, which notes the huge economic power of slaughterhouses in Chicago. There’s high trust, but there’s high risk. Joe ultimately approves the article because he feels that the article also offers a high fulfillment of The Tribune’s goal of bettering the Chicago public.

Phase 7: Agreement

The high risk of the article requires Joe to run it by The Tribune’s Board of Trustees. One member is in the pocket of Big Meat in Chicago and he votes no on running Upton’s article, but the rest of the board members vote yes, and that’s sufficient threshold to provide Agreement.

Phase 8: Fulfillment

The Tribune publishes Upton’s article, “The Jungle”. It appears on the website immediately and in a printed paper the next day.

Phase 9 Inspection

Big Meat in Chicago throws a fit. They claim everything is made up. Snopes.com investigates and rates Upton’s article as “True”.

Phase 10 Dispute

One particular slaughterhouse sues The Tribune and Upton claiming that Upton never visited their slaughterhouse. Upton partially unseals his GPS information, proving that he was there (while still obscuring the exact timestamps, but it’s sufficient for the judge).

Bitcoin

Phase 0: Context

Bob needs to pay an invoice Alice has submitted. He wants to use Bitcoin. Alice and Bob both affirm they have access to Bitcoin. Fees are determined to be low enough as a percentage compared to what Bob needs to send Alice for a Bitcoin transaction to make sense.

Phase 1: Introduction

Bob creates a PSBT that collects together several UTXOs. It will send funds to Alice and send the rest back to his change address, minus a transaction fee.

Phase 2: Wholeness

Bitcoin checks that both of the addresses that Bob is sending to are correctly formed and otherwise ensures that the PSBT is whole (minus signatures).

Phase 3: Proofs

Bitcoin verifies that Bob has access to one of the keys needed to sign the PSBT. But, the UTXOs are locked with multisigs! It warns him that he doesn’t have all the keys necessary to finalize the PSBT!

Phase 4: References

Bitcoin affirms the funds in the UTXOs by looking at their inputs.

Phase 5: Requirements

Bitcoin checks the fee on the PSBT to ensure that it’s high enough for the PSBT to be transmitted in a reasonable amount of time.

Phase 6: Approval

Bob uses his key to sign the PSBT.

Phase 7: Agreement

Bob forwards the PSBT to Carol, who also signs the PSBT. This is sufficient threshold to transmit the full transaction.

Phase 8: Fulfillment

The transaction goes into the mempool, is collected into a block, and the funds are recorded as transferred to Alice’s address.

Phase 9: Inspection

Alice’s exchange, Squiddie, gives her access to the funds when it verifies the block has been confirmed six times.

Phase 10: Dispute

Because Bitcoin prices dropped during the hour and a half that it took the transaction to be entered in a block and then sufficiently confirmed, Alice claims that Bob and Carol didn’t send her enough money. Bob reveals the value of Bitcoin that he recorded, signed, and timestamped at the time the transaction was created, and it shows that Alice was paid the proper amount.

Wellness Data

Phase 0: Context

A clinic considers a new health study that will collect steps records and heart rates to determine the rapidity of the degradation in heart health for users who fall off their fitness plans. They consider the technology of modern activity trackers and determine the accuracy is sufficient for their needs. They also informally poll users to determine whether enough will be willing to participate in the study.

Phase 1: Introduction

Users can choose to sign up by registering anonymized demographic data with the clinc. Their activity trackers then will report initial test data by sending samples of heart rate and step data.

Phase 2: Wholeness

The clinic assesses the format of the test data from each study member to ensure the data format is compatible with their needs. They’re forced to disqualify some members who have very old or very cheap trackers, sometimes because they don’t format data correctly and sometimes because they report too little.

Phase 3: Proofs

Each data entry is signed by the wellness tracker that sent it. The clinic makes sure both a signature and a hash verify the data has not changed.

(If a participant ever submits data that is not properly signed or hashed, all of their data is segregated from the rest of the study.)

Phase 4: References

When the clinic gets test data from a new brand of activity tracker, it must check references. Cryptographically, they affirm the the public key of the brand’s signature against a PKI.

Phase 5: Requirements

The clinic does additional research to audit the data they’re collecting to ensure that it meets community requirements.

Some trackers are reporting too much data, violating community privacy standards and possibly putting the clinic’s HIPAA compliance in question. Their data is rejected from the study.

Further audits determine that some trackers are reporting heart rates or step counts that are more than 10% off, affecting the study’s accuracy. Their data is also rejected.

Phase 6: Approval

Having whittled down their data set to reliable, whole, well-formatted data, the clinic signs an agreement with all remaining volunteers to include their data in their clinical study.

Phase 7: Agreement

Some volunteers are minors, in which case their parents must also sign off.

Phase 8: Fulfillment

The clinic now collects data from remaining participants over a one-year period. It’s sent whenever the participants sync their trackers. Afterward, they publish a paper on the results, eliding and anonymizing much of the data, but maintaining hashes to allow proof of the data in the future.

Phase 9: Inspection

After publication, a statistician does a supplemental study, which cross-references the clinic’s data against their demographic information, revealing new results on how exercise abandonment affects different demographics differently.

Phase 10: Dispute

A doctor claims the study results aren’t accurate after a certain Activity Tracker is determined to have inaccurate results for people with certain skin tones. The clinic partially unelides their clinical data to prove that tracker was not used (because they’d already learned about the inaccuracy in Phase 5).

Educational Credentials

Phase 0: Context

Cyber U. creates a credential program for computer security engineering. They detail their curriculum and the certifications available. cybercat_2382, already an expert in cyber security, considers the reputation of their program decides that a credential would be helpful.

Phase 1: Introduction

Cybercat whizzes through the program, achieves a degree in advanced cybersecurity, and uses that to apply for a job at E-Corp.

Phase 2: Wholeness

E-Corp assesses the structure and format of Cybercat’s credentials to ensure that transcripts, grades, and the diploma are correctly formatted and unaltered.

Phase 3: Proofs

E-Corp checks Cyber U’s signatures of the transcripts and diplomas. Digital badges included in the package are also checked for their authenticity.

Phase 4: References

E-Corp affirms Cyber U’s accreditation as well as the roots of trust used to check their signatures.

Phase 5: Requirements

E-Corp audits Cybercat’s classes to ensure that they meet the expected requirements for a Cyber security degree and that other companies in the space respect Cyber U’s certifications.

Phase 6: Approval

E-Corp’s HR department puts the stamp of approval on the Cyber U credentials, allowing Cybercat’s application to advance.

Phase 7: Agreement

e_mgmt_291 receives Cybercat’s application and decides to set up an interview with them. It’s virtual, of course.

Phase 8: Fulfillment

E-Corp hires Cybercat. Their credentials are entered into the company database.

Phase 9: Inspection

E-Corp sends Cybercat out to a client site. To prove their certification, they sent the client a copy of Cybercat’s credentials, but elided to remove some of Cybercat’s personal data.

Phase 10: Dispute

Ten years on, a class-action lawsuit is filed against Cyber U for negligent misrepresentation, fraud, and breach of contract. Though Cybercat initially had some success with their degree, such as at E-Corp, over time corporate acceptance of Cyber U quickly faded due to the low quality of other recruits. Cybercat joins the class-action suit, revealing enough of their credentials to prove that they were a student there.

Software Supply Chain

Phase 0: Context

Digital-Assets Inc (DAI) considers GitHub as a distribution method for their software and ultimatel determines that it has sufficient trust and is sufficiently pratical to use.

Phase 1: Introduction

DAI produces open-source software called Gordian Guardian, a new asset-protection app. They assert the existence and purpose of a repository for Gordian Guardian and declare the initial (inception) commit and its purpose.

Phase 2: Wholeness

Arthur of Asset Analysis is considering using Gordian Guardian to protect his company’s digital assets. He runs software checks to verify that the repo’s files and metadata are uncorrupted from their origin, ensuring the integrity of the source code. He checks the formatting of source code and metadata to ensure they match the requirements of the repository.

Phase 3: Proofs

Blockchain Commons signs its commits, tags, releases, and other metadata with SSH signatures, ensuring that all changes are verifiable and enabling further validation of the commit history. GitHub clearly shows commits that are Verified. Arthur verfies those and also hand-checks the SHA256 hashes and detached signatures in Gordian Guardian’s newest release.

Phase 4: References

The inception commit for the Gordian Guardian repo acts as a root of trust. When a new engineer begins signing releases, their public key is in turn signed with the private key from the inception commit or else a private key whose public key was previously signed. This creates a chain of trust. When Arthur checks the repo, he can therefore reference signing keys all the way back to the key from the inception commit, via this chain.

Arthur also needs to affirm references for external libraries and dependencies to ensure their reliability. Besides checking their signatures and commits, Arthur also examines these users’ other projects and reads their repo issues to determine their general reputation in the space.

Phase 5: Requirements

Arthur audits whether DAI’s releases meet Asset Analysis’ standards. Do they respond to important Issues within a reasonable amount of time? Do they have a documented code review system and does it meet Asset Analysis’ standards? Is software offered for third-party security review prior to its finalization for use in deployed systems? He likes the answers he gets, so checks off Requirements.

Phase 6: Approval

After checking the validity of DAI’s commits, the profiles of its developers, and the trustworthiness of its third-party libraries, Arthur makes a final call that it’s safe to use Gordian Guardian.

Phase 7: Agreement

Because Gordian Guardian will be used to protect real assets, Arthur needs to get agreement from Asset Analysis’ CFO, which he does.

Phase 8: Fulfillment

Arthur clones the Gordian Guardian repo and builds the app.

Phase 9: Inspection

Twice a year, a third-party is required to inspect Asset Analysis’ asset management, since it includes client assets. Arthur turns over all of his information on Gordian Guardian to the inspectors, and they agree that it meets required certification standards.

Phase 10: Dispute

One of Asset Analysis’ clients complains about their use of an open-source project. Arthur displays to them not just the information he collected on Gordian Guardian, but also the confidential report from the third-party inspectors verifying that it meets certifications standards.

Appendix II: Language Summary

- Phase 0. Context.

- Active Verbs. CONSIDER, plan, survey.

- Objects. INTERACTION, context, ecosystem, environment.

- Phase 1. Introduce.

- Active Verbs. DECLARE, assert, commit, establish, introduce, reveal.

- Objects. ASSERTION, initial claim, inception commit, origin, public declaration.

- Reactive Verbs. ACCEPT.

- Phase 2. Wholeness.

- Preparatory Verbs. STRUCTURE, cohere, order, organize.

- Active Verbs. ASSESS.

- Deprecated Verbs. VALIDATE.

- Objects. INTEGRITY, consistency, wholeness.

- Phase 3. Proofs.

- Preparatory Verbs. ENCODE, hash, sign.

- Active Verbs. VERIFY, authenticate.

- Objects. SECRET, hash, proof, signature

- Phase 4. References.

- Preparatory Verbs. ENDORSE [entity].

- Active Verbs. AFFIRM, Aggregate, check, look up, synthesize.

- Objects. TRUST, declarations, references, trust model.

- Phase 5. Requirements.

- Request Verbs. AUDIT [requirements], check [standards], request [requiements].

- Additional Parties. COMMUNITY, peers.

- Active Verbs. COMPLY, cerify, standardize, test.

- Objects. REQUIREMENTS, expectations, policies.

- Phase 6. Approval.

- Active Verbs. APPROVE, authorize, OK.

- Objects. RELEASE.

- Related Verbs. CALCULATE [risk].

- Related Objects. RISK MODEL.

- Phase 7. Agreement.

- Request Verbs. REQUEST [approval].

- Additional Parties. SIGNER.

- Active Verbs. AGREE, endorse [approval].

- Objects. THRESHOLD, release.

- Phase 8. Fulfillment.

- Active Verbs. FINALIZE, fulfill.

- Objects. INTERACTION.

- Phase 9. Escalation.

- Request Verbs. ESCALATE, request [inspection]

- Additional Parties. INDEPENDENT THIRD-PARTY.

- Active Verbs. INSPECT, approve, confirm.

- Phase 10. Dispute.

- Request Verbs. DISPUTE.

- Additional Parties. INDEPENDENT THIRD-PARTY.

- Active Verbs. ARBITRATE.

Versions

- v1.0 (11/13/24): Initial release on web site. (Previous versions existed in HackMD.)

- v1.1 (2/5/25): Language updates. Removed VALIDATE from p2, changed core verb in p4 from AGGREGATE to AFFIRM, changed core verb in p5 from CHECK to AUDIT.